The Famous Black Caterers of Philadelphia

By Neenah Payne

By Neenah Payne

How African Rice Growers Enriched America! describes how the knowledge and skills of enslaved African rice agronomists created the legendary “Carolina Gold” which made South Carolina so wealthy.

Film — High on The Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America explains that Black Americans have played an essential but unacknowledged role in American cuisine for centuries. In four episodes, culinary experts discuss the history of African foods and their relationships to American foods. The docuseries is based on the book High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America by Jessica B. Harris. Season 1 of High on the Hog covers the first part of the book. Season 2 which is expected be released in 2023 may cover the second half of the book. From pages 117-122, the book discusses the amazing role of Black caterers in Philadelphia in the 19th century.

Watch High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America

Henry Dorsey: Philadelphia’s First Black Historian

While Thomas Downing reigned as the Oyster King of New York from 1830-1860, Black caterers ruled Philadelphia in the 19th century. High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America discusses Downing in pages 122-125.

The book points out:

I will also speak of presidential chefs like George Washington’s Hercules and Thomas Jefferson’s James Hemings and of an alternative African American culinary thread that weaves through the fabric of our food. This parallel thread is a strong one and includes Big House cooks who prepared lavish banquets, caterers who created a culinary co-operative in Philadelphia in the nineteenth century, a legion of black hoteliers and culinary moguls, and a growing black middle and upper class….My family is a part of that middle class and encapsulates both culinary threads… The Jones side of the family always held reunions at table…..

Book – William Dorsey’s Philadelphia and Ours: On the Past and Future of the Black City in America

Amazon Description

Lane here illuminates the African-American experience through a close look at a single city, once the metropolitan headquarters of black America, now typical of many. He recognizes that urban history offers more clues, both to modern accomplishments and to modern problems, than the dead past of rural slavery. The book’s historical section is based on hundreds of newly discovered scrapbooks kept by William Henry Dorsey, Philadelphia’s first black historian.

These provide an intimate and comprehensive view of the critical period between the Civil War and about 1900, when African-Americans, formally free and increasingly urban, made the biggest educational and occupational gains in history. Dorsey’s tens of thousands of newspaper clippings and other sources, detail records of high culture and low, success and scandal, personal and public life. In the final chapters Lane outlines the urban situation today, the strong parallels between past and present that suggest the power of continuity and the equally strong differences that point to the possibility of change.

First Black Philadelphia Caterer: Robert Bogle

Entrepreneur Robert Bogle was the first of many African American caterers who served nineteenth-century Philadelphia’s white elite. Born in 1774, the 1810 federal census shows Bogle and five members of his family in Philadelphia’s South Ward, where the majority of the city’s African American residents lived. The censuses of 1820 and 1830 record that the Bogles remained in the South Ward as their family increased. A successful businessman, Bogle died in 1848, remembered by prominent citizens in verse and memoir as an essential presence at all of life’s main events, from christenings to funerals.

Robert Bogle established his shop at 46 South Eighth Street in 1812 and is credited with having “virtually created the business of catering” in Philadelphia by W.E.B. DuBois, although the term “caterer” was not used until the 1860s. In the mid-nineteenth century, the growing African American population of Philadelphia was facing competition from Irish immigrants for service sector jobs. Philadelphia was rocked by race riots in the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s. Catering and other food trades offered African Americans the opportunity to own their own businesses with little competition from whites. African American catering companies played a prominent role in Philadelphia’s social life for more than 150 years, from Bogle’s early-nineteenth-century establishment until Albert E. Dutrieulle Catering closed in 1967.

In addition to catering, Robert Bogle ran a funeral business for the social elite. “Ode to Bogle,” a light poem written in 1829 by prominent Philadelphia banker Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), describes Bogle as an important contributor to any social event. “Thy reign,” the verse explains, “begins before our earliest breath, nor ceases with the hour of death.” The poem describes the caterer as a calm, unruffled administrator of sweet treats and funeral processions, a “Colourless colored man, whose brow; Unmoved, the joys of life surveys; Untouched the gloom of death displays.”

High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America discusses Bogle on pages 118-119.

Robert Bogle and Philadelphia’s Dynastic Black Caterers

Image from the Library Company of Philadelphia

Philadelphia’s Food Service History is Black History

You might have noticed on South 8th Street a historical marker that reads: “A noted Black caterer, [Robert] Bogle opened a posh eatery at this location in 1813. Recognized for his popular meat pies, he was well known as a master of ceremonies at elaborate weddings, funerals, and banquets for his wealthy clients.” This sign marks not only the location of his food establishment, but the birthplace of the catering industry as we know it today.

Prior to Bogle, catering (as it came to be called only in the 1860s) was organized and executed by private cooks and servants to the wealthy. But there also existed the public butler or waiter—usually a free person of color employed by several households. Sidestepping competition with Irish-Americans in other hospitality service sectors, Bogle appropriated this role of the public butler to corner the market for food service at large social gatherings. When he added his culinary talent, social capital, and entrepreneurial skills, Bogle could only stand to revolutionize the way Philadelphia hosted weddings, banquets, christenings, and funerals….

Bogle became a leader of the African American community and was praised for his social fluidity and business acumen. He accessed influence too through his establishment, the Blue Bell Tavern, which became the regular meeting place for politicians and Philadelphia’s social elite. Bogle’s new industry gave the African American community entry into higher social and economic echelons as chefs, servers, and entrepreneurs, and paved an avenue for the empire of Black-owned-and-operated catering companies that succeeded his….

Bogle is credited not only with the birth of an entire industry, but the creation of the Guild of Caterers and training some of the heads of subsequent great Black catering companies: the Prossers, Thomas Dorsey (Jones, Dorsey, and Minton), Jeffery Chew, St. John Appo, and Peter Augustin(e), who inherited Bogle’s throne as Philadelphia’s catering king. Augustine’s venture and high-society restaurant made Philadelphia catering famous nationwide and his kin intermarried other Haitian catering families to make a true dynasty that ended in the 1960s with the Dutrieulle family.

Amazon Description

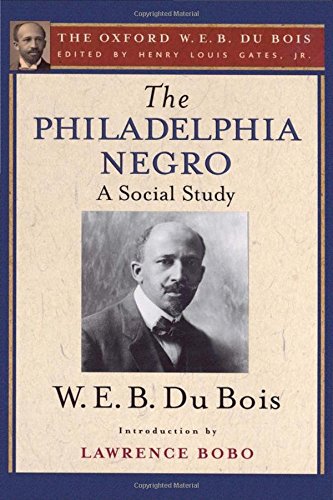

W. E. B. Du Bois was a public intellectual, sociologist, and activist on behalf of the African American community. He profoundly shaped black political culture in the United States through his founding role in the NAACP, as well as internationally through the Pan-African movement. Du Bois’s sociological and historical research on African-American communities and culture broke ground in many areas, including the history of the post-Civil War Reconstruction period.

Du Bois was also a prolific author of novels, autobiographical accounts, innumerable editorials and journalistic pieces, and several works of history. First published in 1899 at the dawn of sociology, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study is a landmark in empirical sociological research. Du Bois was the first sociologist to document the living circumstances of urban Black Americans. The Philadelphia Negro provides a framework for studying black communities, and it has steadily grown in importance since its original publication. Today, it is an indispensable model for sociologists, historians, political scientists, anthropologists, educators, philosophers, and urban studies scholars. With a series introduction by editor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and an introduction by Lawrence Bobo, this edition is essential for anyone interested in African American history and sociology.

Catering says:

The catering business is closely related to restaurants, though many caterers work from a rented or home-based kitchen. Frequently caterers have been – and are — cooks or waiters; many later enter the restaurant business as proprietors. Then, as now, catering provides an important financial supplement to restaurants. In the 18th and 19th centuries many coffee houses, taverns, eating houses, refectories, etc., not only catered to groups in their own banquet rooms or off-site, but also delivered food to homes and workplaces.…

The early Delmonico café of the 1830s supplied meals to residents of a small hotel located next door on Broad Street in New York…. African-Americans were quite prominent in the catering business until the latter part of the 19th century. They could be found in Boston, Salem, New York, Washington, Baltimore, Charleston, and other cities along the East Coast, but especially in Philadelphia. Quite a few earned prestige catering to elite white patrons, often being referred to as “princes.” They were often rumored to have become quite wealthy.

Caterers: Henry Jones, Thomas Dorsey, and Henry Minton

Catering adds:

According to W. E. B. DuBois in The Philadephia Negro (1899), “the triumvirate [Henry] Jones, [Thomas] Dorsey and [Henry] Minton ruled the fashionable world from 1845-1875.” Dorsey had been a slave, as had the celebrated caterer Joshua B. Smith, who was Boston’s top man in the field. At the opening of Smith’s new restaurant in 1867, the entire city government was present and former mayor Josiah Quincy gave a speech.

But despite the prominence and success of Black caterers, the fact that they served clients in high society, and the praise heaped upon them for their astute management and taste, they were still regarded as second-class citizens banned from public transportation in Philadelphia as well as theaters and cemeteries there and elsewhere.

According to the 1870 U.S. federal census, there were then about 154 caterers (undoubtedly an undercount), 129 of whom were born in the U.S. The majority of those born in this country whose race was identified were Black (56) or Mulatto (29). But by the end of the 19th century, Black caterers had become less numerous, with much catering having been taken over by the big hotels that by then were dominant in the field, particularly for large banquets.

Black History Month: Caterers of the 1800s

In the mid-1800s, black caterers Thomas Dorsey, Henry Jones, and Henry Minton established a catering monopoly in Philadelphia, an obvious economic achievement. Dorsey, in particular, led a quite spectacular rise to prominence. Born into slavery in 1812, he was fettered through his early adulthood by a Maryland planter. He managed to escape from bondage in his early twenties and fled to Pennsylvania which was a free state.

Although Dorsey was uneducated, his naturally refined instincts and amiable character impressed all who had the privilege of meeting him. He quickly found himself with several valuable friends. After he was recaptured and returned to the plantation in Maryland, these friends raised funds to purchase his freedom and bring him back to the city where he was loved.

During the tense years that followed, Dorsey’s ability to navigate the repression of free blacks from the industrial jobs available at that time and the growing racial conflict afforded him success in the catering industry. As much of the African American community were blocked from other types of employ, free blacks found themselves in a type of mandatory entrepreneurship that widely centered on foodservice and catering.

With impeccable manners and a taste for unusual flavor pairings, plus the self-reliance to demand prosperity, Dorsey and his fellows circumnavigated the closed doors that society put in their path, establishing a foothold in the upscale catering market in Philadelphia and beyond.

Jones, Dorsey, and Minton became household names through much of this era and were known to command as much as $50 a plate. They all owned profitable restaurants as well.

The bright and vivid start to the great production of events where food was the centerpiece, and the cooks and wait staff were cunning, elegant, and black began even earlier. Many of those noted as the influencers to the industry trained under a man who was a true mentor of hospitality, Peter Augustin.

In 1818, the Haitian refugee purchased the already successful business of Robert Bogle, the first person of African descent to cater to Philadelphia’s white elite, and elevated it even further. By providing china, tablecloths, tables, chairs, and other event accouterments for rent to his clients, he became one of the first event rental moguls in the US.

While Philadelphia was the unofficial center for blacks in catering, the movement surged up and down the eastern coast of the US. With the talent and skill to cook for large numbers, manage costs through training staff to handle many different jobs, and the instilled etiquette needed to handle any and all clientele, black caterers were influential in many American cities after the civil war.

When black caterers held a lofty status

Philadelphia Inquirer 2/17/99

They were among the worst of times to be black in Philadelphia, the 1840s slum housing was frightful and race riots swept the city. A particularly deadly confrontation was touched off when a white mob attacked a black man who had a white wife, torching homes on Sixth Street; one black and three whites were killed. But there is another face to the history of that era, one that is considerably more optimistic, even transcendent the triumphant face of the black caterer.

The Philadelphia caterers’ guild, sociologist W.E.B. DuBois would later observe, came to rival in power and prestige the craft guilds of medieval Europe. In fact, that was the golden age of black catering, though it is so unsung that even today’s practitioners of the craft have never heard of it….It is a tale both inspirational and, in the end, cautionary a missing moment in what most Philadelphians know about the city’s grand and colorful culinary history.

Indeed, for a time, DuBois notes, one simply did not indulge in lobster salad, chicken croquettes, deviled crabs or terrapin at an affair unless they were prepared by the hand of a black …But it would not be until the 1790s, in the person of Robert Bogle, that the craft took on a new dimension. By introducing the catering contract and carefully training his cooks, Bogle all but invented the city’s catering business. He used a brilliant form of economic jujitsu, transforming one of the few trades in which blacks were relatively unchallenged — domestic service — into a business they directed and controlled.

In his seminal study The Philadelphia Negro 100 years ago, DuBois concluded that those early caterers “shrewdly, persistently and tastefully . . . transformed the Negro cook and waiter into the public caterer and restaurateur, raising a crowd of unpaid menials to become a set of self-reliant, original businessmen,” amassing fortunes and wide respect.

By the end of the 19th century, the tide had ebbed Philadelphia society was taking its cue from New York, not local trend-setters; it took larger amounts of capital to get into big-time catering; and palatial hotels inhospitable to black entrepreneurs were taking bigger shares of the business. New waves of immigrants, too, among them the Irish, were competing for a piece of the pie, even as family-centered caterers found themselves catering not to the extravagantly rich anymore, but to a lower-profit middle-class market.

Still, it had been an extraordinary run, a time, as DuBois writes, when black caterers Henry Jones and Henry Minton ruled the social world of Philadelphia through its stomach and, in the dark days of the 1840s, the delicacies of a West Indian immigrant named Peter Augustin made the reputation of Philadelphia catering famous the nation over.

See: Robert Bogle Thomas Dorsey caterers.

Dutrieuille Family

How this Black Philly chef helped create the modern catering industry

For 50 years, Albert E. Dutrieuille cooked for the city’s elite from his house on Spring Garden.

A newspaper clipping from the 1930s featured the Dutrieuilles’ extended family COURTESY HARRY AND LAUREN MONROE

When Lauren Monroe first saw photographs of her great-great-grandfather Albert E. Dutrieuille and his family, elegantly dressed and posing around Philadelphia with an air of carefree sophistication, she did a double take. “I remember looking at the photos and thinking, ‘Black people lived like this?‘” Monroe told Billy Penn. “You grow up thinking the Black experience is one way, but… These aren’t images you always see of Black culture.” You did see them in early 20th century Philadelphia. Throughout the early 1900s, the city was home to a flourishing African American high society, in which Monroe’s ancestors figured prominently.

Florence May Dutrieuille (Albert’s wife) with daughters Fannie and Marian

COURTESY HARRY AND LAUREN MONROEDutrieuille, it turns out, was considered one of the last of the “great caterers of Philadelphia,” a cohort credited with kickstarting the modern American catering industry. It’s a career he picked up from his father, P. Albert Dutrieuille — whom newspapers of the era called “world-famous” — and one he solidified by establishing dining standards for the Olde Philadelphia Club, which he helped found.

But fame in one era can turn quickly to anonymity in the next, and for the past several decades, Dutrieuille’s story remained mostly untold. It would take the death of Monroe’s father’s cousin last December to rustle the dust from the family legacy — via a trove of archives discovered in the family house at 40th and Spring Garden. The basement there had apparently.

Left: Albert P. Dutrieuille; Right: The house at 4001 Spring Garden

“They went down and everything was still there,” Monroe said, describing a room full of chafing dishes, pots and pans silverware and other artifacts. What she really wanted to know from her relatives who sorted through the stuff: “Did you find any menus?”

Monroe, who works in communications in New York City, took the menus to Harlem chef Melba Wilson. Together, the women used them as inspiration for a Black History Month dinner at Melba’s designed to be both educational and delicious.

“If I, as a family member, didn’t know that Blacks helped form the modern day catering industry — which is a huge industry these days — many others might also not know,” Monroe explained.

What’s being served? Wilson isn’t recreating one of Dutrieuille’s dinners exactly, but she’s pulling from some of the staples seen on the placards discovered in the Spring Garden house. Over his half-century of cooking, Dutrieuille burnished his reputation for high-end fare, which he served at white-tablecloth banquets for elites both Black and white, according to African-American Business Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary. He also reportedly had a special relationship with the Catholic Church, and catered many church-related affairs and celebrations.

One such event, held in November 1939 at St. Charles Borromeo’s Roman church in the current neighborhood of Point Breeze, featured no fewer than eight different courses. Dutrieuille wowed his dinner guests with delicacies like exotic fresh fruits, sherbert palate cleansers, Parisienne-style potatoes, English rolled chops, crab-stuffed flounder, cheese plates, fresh lettuce and tomato salads, and “fancy ice creams” before the coffee service, with mints and salted nuts.

COURTESY HARRY AND LAUREN MONROE

Guests at the Black History Month dinner in NYC should expect a riff on that style of food, per Monroe. “When I texted Melba these photos, she said ‘This is amazing!’ and immediately jumped on board.”

Though she’s thrilled to have this opportunity to spread the word of her family’s impressive culinary heritage, Monroe is sad the West Philadelphia home has been sold. “It was [my relative’s] wish to sell it, I’ve never even been there!” she explained. “I would go to Philly a couple times a year, and at no point did they say oh hey, let’s swing by this house that’s been in our family for 100 years.”

Since she’s been traveling back and forth to help donate materials to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania recently, she plans to try to connect with the new owners. “I’ve been meaning to reach out…and see if they are aware of the deep history in that house,” Monroe said. “There’s so much there that’s relevant to our times.”

GASTRONOMIC ALCHEMY: HOW BLACK PHILADELPHIA CATERERS TRANSFORMED TASTE INTO CAPITAL, 1790-1925

Gregory Hargreaves interviews Danya Pilgrim about her book project “Gastronomic Alchemy: How Black Philadelphia Caterers Transformed Taste into Capital, 1790-1925.” In support of her research, Pilgrim, assistant professor at Temple University, received exploratory and Henry Belin du Pont research grants from the Hagley Center for the History of Business, Technology, & Society.

In “Gastronomic Alchemy,” Pilgrim reveals the development and efflorescence of a Philadelphia catering industry owned and operated by African American waiters, brokers, cooks, & others. Through their work, black caterers earned economic success and cultural influence in Philadelphia that combined to form meaningful capital, which helped to create and support a vibrant black community. By uncovering this process of capital formation, Dr. Pilgrim “illuminates how one group of African Americans fought for self-determination in every aspect of their lives.”

See: How Black Chefs Paved the Way for American Cuisine: A look at the key culinary influencers, from the 17th century until now.

Henry Jones’ Amazing Will

The book Black Society by Gerri Majors points out that the catering industry was created by a Philadelphia Black man, Robert Bogle, in the early 1800s. Black Philadelphia caterers became famous throughout the country and it became the “in thing” to have affairs catered by “caterers of color”.

Henry Jones escaped slavery in the West Indies at age 12 and went to Philadelphia where he worked in a livery stable. He had one of the best catering firms in the city and belonged to a group of African American men who dominated the catering business in 19th century Philadelphia. He opened a restaurant in 1845. Jones was active in the abolitionist movement and joined the Social, Civil, and Statistical Association (SCSA) of the Colored People of Pennsylvania.

With the revenue from his catering business, Jones invested heavily in real estate and owned several blocks of houses. Lawyers say that Jones’ will is one of the finest and cleverest ever drawn up in Landsdale County, Pa. where he lived. His will made provisions for the dispersal of an estate of over $300,000 that provided the next three generations with ample funds. To his own six children, Jones left the interest on the estate. The interest itself was sufficient to allow each of them to live with financial ease. He had also purchased property for each of them.

Jones’ will specified that his estate was to be settled when his last child died which occurred with the death of Emma Jones Warrick on Friday, January 13, 1923. Then the estate was divided equally among the families of the six Jones children. Emma’s 1/6 share went to her 3 children – William, Blanche, and Meta.

Since Blanche Cardozo had died in 1911, her money went to her six children (one of whom was my mother). Each received approximately $8,000 which would be worth about $138,500 in 2022. Since each of Blanche’s children received the equivalent of $138,500 today, Blanche’s share was worth about $831,000. However, that was just one third of her mother Emma’s share which would have been worth $2,493.000. Yet, Emma’s share was just 1/6 of the total estate which was worth about $14,958.000.

Neenah Payne writes for Activist Post and Natural Blaze