Why We Must Be Honest This Thanksgiving

By Neenah Payne

By Neenah Payne

Thanksgiving is one of the most popular holidays in America. More people travel to be with family for Thanksgiving than at any other holiday. We look forward to the terrific foods — especially the turkey. It’s a “feel good” holiday because we are told that it commemorates the “First Thanksgiving” which the Pilgrims shared with Native Americans.

However, this story fails to acknowledge that Thanksgiving is a Day of Mourning for many Native Americans. If this is a celebration of our collaboration and unity, why it is not also a joyful holiday for everyone? What’s missing in this story and why is it so important for us to understand that now?

Dr. Zach Bush warns that we are in the Sixth Great Extinction and human survival depends on the urgent restoration of our soils (earth). So, the world — led by the West — is in very grave trouble now. Where will we find the inspiration to change our relationship to the Earth on which we depend for survival?

Our View of Native Americans Will Determine Our Fate

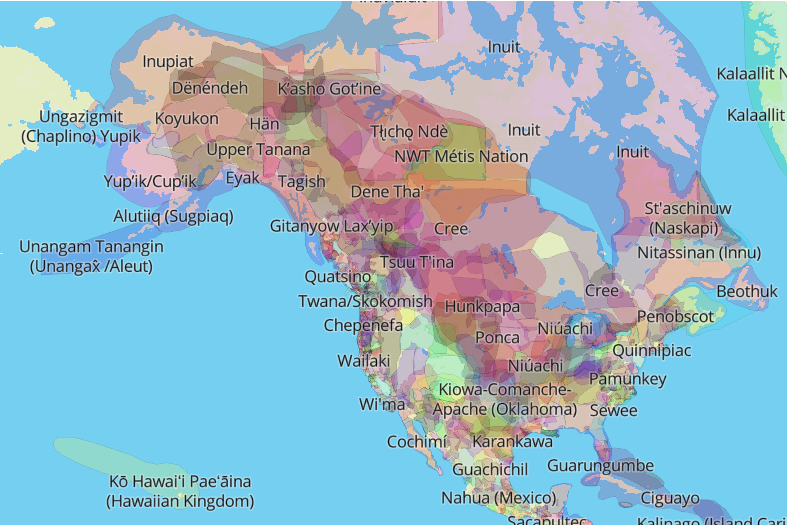

There are 500 Native Nations in this hemisphere — many of which have been here tens of thousands of years. Can these ancient wisdom keepers be a source of inspiration and guidance now? Many Americans think so as they flock to the Amazon to drink ayahuasca with shamans. However, although many of our states, cities, and rivers carry Native names, most Americans ignore the existence of Native America and know little about these cultures. Yet, our survival now depends on our willingness to learn from them.

Native America’s Gifts To The World shows some of the profound gifts Native America gave the world. Philip P. Arnold, a member of Neighbors of the Onondaga Nation (NOON) and associate professor of indigenous religions at Syracuse University, says:

“How we in the larger society regard indigenous peoples — who have an ongoing relationship with the living earth — will determine our ability to survive.”

Indian Givers: How Native Americans Transformed the World by Jack Weatherford explains the great debt the world owes Native America for foods, medicines, concepts of religious and political freedom, philosophy, etc. In 1988, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution recognizing the influence of the Iroquois League on the formation of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Chief Oren Lyons of the Haudenosaunee is co-editor of Exiled in the Land of the Free: Democracy, Indian Nations, and the U.S. Constitution. This book, written into the Congressional Record and adopted for courses at 12 universities, presents the strongest case ever made for Native American sovereignty and has major implications for relations between Indian nations and the United States.

For Native Peoples, Thanksgiving Isn’t A Celebration. It’s A National Day Of Mourning says:

“This Thanksgiving, Kisha James asks non-Native people to educate themselves and their families on the real history of the holiday. Take time to learn the tribe whose land you’re on, then look into the tribe’s struggles and donate to help, she says. ‘Try to divorce your Thanksgiving celebrations from the Thanksgiving mythology,’ she says. ‘So no more pilgrims and Indians, no more teaching your children about the first Thanksgiving as we learn it in public school where it was a friendly meal.’ And don’t think about Indigenous people only on Thanksgiving, she says.”

Frank James: National Day of Mourning

Frank James and the history of the National Day of Mourning explains:

“Fifty years ago, a proud Native American man called Frank James took a stand. He took a stand against centuries of history that told a story that simply was not true. A legacy that gave his people no voice. In 1970, Frank James was the leader of the Wampanoag, the people who in 1620 watched as a strange ship from the east arrived on the coast of their lands.

Some 350 years on, he refused to be silenced about the treatment of his people since the landing of the Mayflower. He had been invited to a Thanksgiving state dinner to mark the anniversary of the Mayflower’s sailing, as part of a celebration that embraced the misleading schoolbook narrative of the Pilgrims’ relationship with the Wampanoag that culminated in a great feast.

He was asked to give a speech to mark the occasion, one the organisers requested to read beforehand to check its content. James wrote a scathing indictment of the Pilgrims. He described how they desecrated Native American graves, stealing food and land and decimating the population with disease. The speech was deemed inappropriate and inflammatory and James was given a revised speech. He refused to read it. He vowed that the Wampanoag and other Native peoples would regain their rightful place and was ‘uninvited’ from the programme.

Instead, supporters followed James to hear him give his original speech on Cole’s Hill, next to the statue of former Wampanoag leader Ousamequin. This became the first official National Day of Mourning. The same year, James founded the United American Indians of New England, a progressive Native American activist group.”

The article adds:

“Who was Frank James? Frank James was born in 1923 and, for a time, was the leader of the Wampanoag people. James was considered a Renaissance man by many who knew him. He was a gifted painter, scrimshaw artist, silversmith, draftsperson, builder, raconteur, model ship-maker, fisher and sailor. He was also an excellent trumpet player and is thought to be the first Native American graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music, doing so in 1948.

However, while many of his classmates secured positions with top symphony orchestras, James was told that, due to segregation and racism, no orchestra in the US would hire him because of the colour of his skin. In 1957, he became a music teacher on Cape Cod. James was a very popular and influential instructor and went on to become the director of music of the Nauset Regional Schools – a position he held for more than 30 years.

Also known as Wamsutta, James devoted much of his life to fighting against racism and for the rights of all Indian people. In 1970, James cemented his place in history when he organised the first National Day of Mourning, on the 350th anniversary of the Mayflower landing in America.”

THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG

To have been delivered at Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1970

“I speak to you as a man — a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction (“You must succeed — your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community!”). I am a product of poverty and discrimination from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome, and to some extent we have earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first — but we are termed “good citizens.” Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to be so.

It is with mixed emotion that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you — celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back, of reflection. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People. Even before the Pilgrims landed, it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans. Mourt’s Relation describes a searching party of sixteen men. Mourt goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indians’ winter provisions as they were able to carry.

Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people.

What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years?

History gives us facts and there were atrocities; there were broken promises — and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries, but never before had we had to deal with fences and stone walls. But the white man had a need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only ten years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the souls of the so-called “savages.” Although the Puritans were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other “witch.”

And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands taken and, in token, reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could only stand by and watch while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian could not understand; for to him, land was survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It was not to be abused. We see incident after incident, where the white man sought to tame the “savage” and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early Pilgrim settlers led the Indian to believe that if he did not behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again. The white man used the Indian’s nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman — but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man’s society, we Indians have been termed “low man on the totem pole.”

Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives — some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokee and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoag put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man’s way for their own survival. There are some Wampanoag who do not wish it known they are Indian for social or economic reasons.

What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and live among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they live as “civilized” people? True, living was not as complex as life today, but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their [the Wampanoags’] daily living. Hence, he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious, and dirty.

History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt, and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood.

The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be the image the white man has created of the Indian; his “savageness” has boomeranged and isn’t a mystery; it is fear; fear of the Indian’s temperament! High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of our great Sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man caused us to be silent.

Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We ARE Indians! Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the whites did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American prisoners of war in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently.

Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting. We’re standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass, we’ll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us. We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail.

You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later, it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian. There are some factors concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across this vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as a white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs.

We’re being heard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have the unique culture, we still have the will and, most important of all, the determination to remain as Indians. We are determined, and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only the beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours.

Wamsutta

September 10, 1970”

Neenah Payne writes for Activist Post and Natural Blaze

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.