Corporate Concentration in the US Food System Makes Food More Expensive and Less Accessible for Many Americans

By Philip H. Howard, Michigan State University and Mary Hendrickson, University of Missouri-Columbia

By Philip H. Howard, Michigan State University and Mary Hendrickson, University of Missouri-Columbia

Agribusiness executives and government policymakers often praise the U.S. food system for producing abundant and affordable food. In fact, however, food costs are rising, and shoppers in many parts of the U.S. have limited access to fresh, healthy products.

This isn’t just an academic argument. Even before the current pandemic, millions of people in the U.S. went hungry. In 2019 the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated that over 35 million people were “food insecure,” meaning they did not have reliable access to affordable, nutritious food. Now food banks are struggling to feed people who have lost jobs and income thanks to COVID-19.

As rural sociologists, we study changes in food systems and sustainability. We’ve closely followed corporate consolidation of food production, processing and distribution in the U.S. over the past 40 years. In our view, this process is making food less available or affordable for many Americans.

[do_widget id=text-16]

Fewer, larger companies

Consolidation has placed key decisions about our nation’s food system in the hands of a few large companies, giving them outsized influence to lobby policymakers, direct food and industry research and influence media coverage. These corporations also have enormous power to make decisions about what food is produced how, where and by whom, and who gets to eat it. We’ve tracked this trend across the globe.

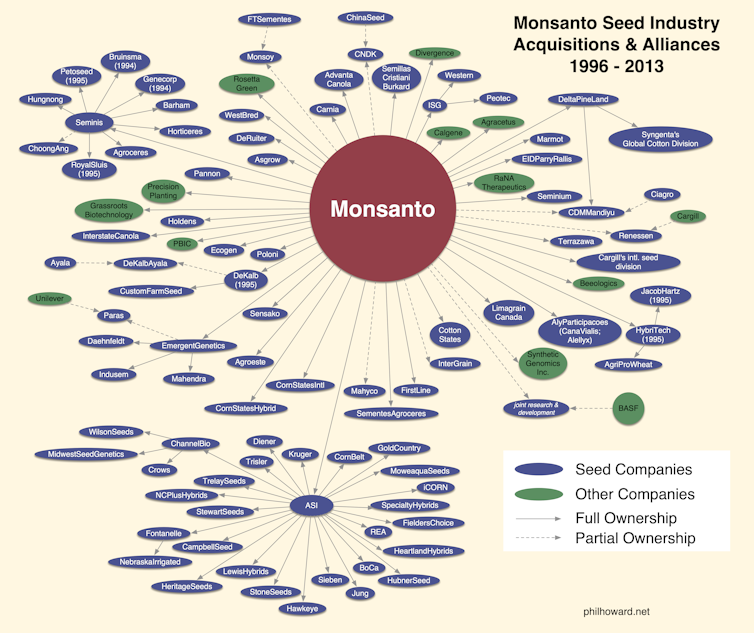

It began in the 1980s with mergers and acquisitions that left a few large firms dominating nearly every step of the food chain. Among the largest are retailer Walmart, food processor Nestlé and seed/chemical firm Bayer.

Between 1996 and 2013 Monsanto acquired more than 70 seed companies, before the firm was itself acquired by competing seed/chemical firm Bayer in 2018. Philip Howard, CC BY-ND

Some corporate leaders have abused their power – for example, by allying with their few competitors to fix prices. In 2020 Christopher Lischewski, the former president and CEO of Bumblebee Foods, was convicted of conspiracy to fix prices of canned tuna. He was sentenced to 40 months in prison and fined US$100,000.

In the same year, chicken processor Pilgrim’s Pride pleaded guilty to price-fixing charges and was fined $110.5 million. Meatpacking company JBS settled a $24.5 million pork price-fixing lawsuit, and farmers won a class action settlement against peanut-shelling companies Olam and Birdsong.

FREE PDF: 10 Best Books To Survive Food Shortages & Famines

Industry consolidation is hard to track. Many subsidiary firms often are controlled by one parent corporation and engage in “contract packing,” in which a single processing plant produces identical foods that are then sold under dozens of different brands – including labels that compete directly against each other.

Recalls ordered in response to food-borne disease outbreaks have revealed the broad scope of contracting relationships. Shutdowns at meatpacking plants due to COVID-19 infections among workers have shown how much of the U.S. food supply flows through a small number of facilities.

With consolidation, large supermarket chains have closed many urban and rural stores. This process has left numerous communities with limited food selections and high prices – especially neighborhoods with many low-income, Black or Latino households.

Widespread hunger

As unemployment has risen during the pandemic, so has the number of hungry Americans. Feeding America, a nationwide network of food banks, estimates that up to 50 million people – including 17 million children – may currently be experiencing food insecurity. Nationwide, demand at food banks grew by over 48% during the first half of 2020.

Simultaneously, disruptions in food supply chains forced farmers to dump milk down the drain, leave produce rotting in fields and euthanize livestock that could not be processed at slaughterhouses. We estimate that between March and May of 2020, farmers disposed of somewhere between 300,000 and 800,000 hogs and 2 million chickens – more than 30,000 tons of meat.

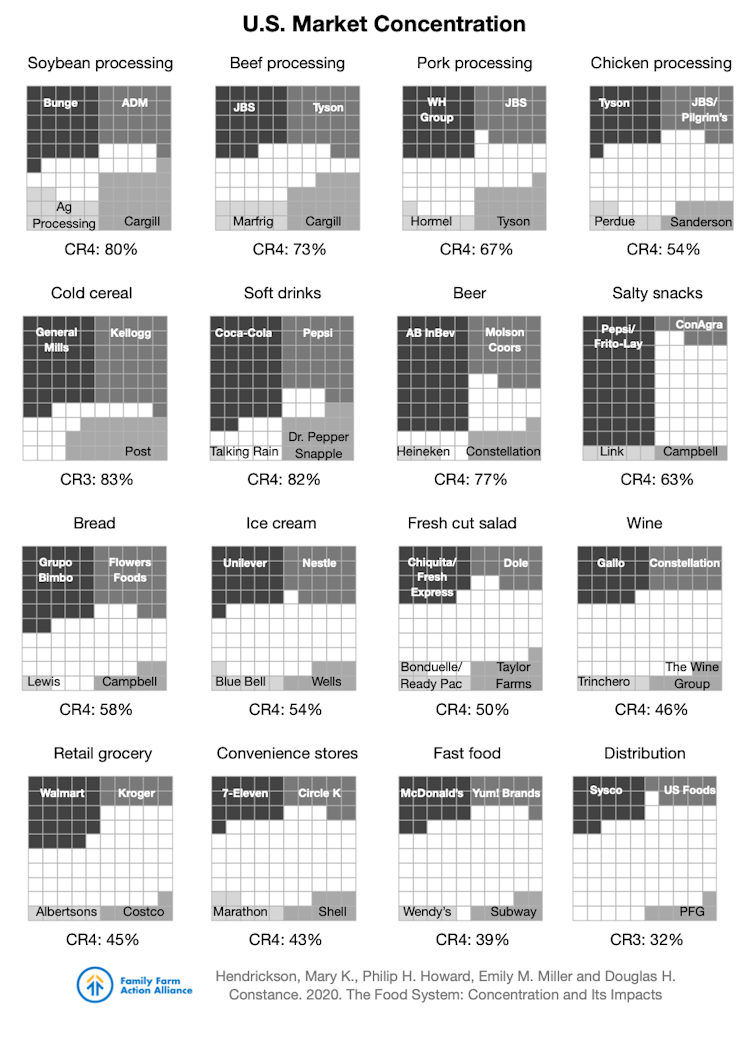

What role does concentration play in this situation? Research shows that retail concentration correlates with higher prices for consumers. It also shows that when food systems have fewer production and processing sites, disruptions can have major impacts on supply.

Consolidation makes it easier for any industry to maintain high prices. With few players, companies simply match each other’s price increases rather than competing with them. Concentration in the U.S. food system has raised the costs of everything from breakfast cereal and coffee to beer.

The combined share of sales for the top four firms (CR4) for selected U.S. commodities, food processing/manufacturing and distribution/retail channels. Family Farm Action Alliance, CC BY-ND

As the pandemic roiled the nation’s food system through 2020, consumer food costs rose by 3.4%, compared to 0.4% in 2018 and 0.9% in 2019. We expect retail prices to remain high because they are “sticky,” with a tendency to increase rapidly but to decline more slowly and only partially.

We also believe there could be further supply disruptions. A few months into the pandemic, meat shelves in some U.S. stores sat empty, while some of the nation’s largest processors were exporting record amounts of meat to China. U.S. Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Cory Booker, D-N.J., cited this imbalance as evidence of the need to crack down on what they called “monopolistic practices” by Tyson Foods, Cargill, JBS and Smithfield, which dominate the U.S. meatpacking industry.

Tyson Foods responded that a large portion of its exports were “cuts of meat or portions of the animal that are not desired by” Americans. Store shelves are no longer empty for most cuts of meat, but processing plants remain overbooked, with many scheduling well into 2021.

Toward a more equitable food system

In our view, a resilient food system that feeds everyone can be achieved only through a more equitable distribution of power. This in turn will require action in areas ranging from contract law and antitrust policy to workers’ rights and economic development. Farmers, workers, elected officials and communities will have to work together to fashion alternatives and change policies.

The goal should be to produce more locally sourced food with shorter and less-centralized supply chains. Detroit offers an example. Over the past 50 years, food producers there have established more than 1,900 urban farms and gardens. A planned community-owned food co-op will serve the city’s North End, whose residents are predominantly low- and moderate-income and African American.

The federal government can help by adapting farm support programs to target farms and businesses that serve local and regional markets. State and federal incentives can build community- or cooperative-owned farms and processing and distribution businesses. Ventures like these could provide economic development opportunities while making the food system more resilient.

In our view, the best solutions will come from listening to and working with the people most affected: sustainable farmers, farm and food service workers, entrepreneurs and cooperators – and ultimately, the people whom they feed.![]()

Philip H. Howard, Associate Professor of Community Sustainability, Michigan State University and Mary Hendrickson, Associate Professor of Rural Sociology, University of Missouri-Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Top image: Volunteers prepare boxes at the Greater Boston Food Bank on Oct. 1, 2020. Iaritza Menjivar, The Washington Post via Getty Images